For New Practitioners:

Here are three articles originally submitted to the Vasectomy Network Google Group that WVD feels will be useful to those of you who are just beginning to practice.

Three Lessons I Wish I’d Known When I Started Performing Vasectomies

By Dr. Jean-Philippe Bercier, MD, Ottawa, Canada

vasectomy.ca

Starting a vasectomy practice can feel both exciting and overwhelming. Between mastering technique, choosing the right instruments, keeping your data organized, and managing patient flow, there’s a lot to balance — especially in the early years.

With time, volume, and many lessons learned, I’ve refined my workflow and now perform 4,000–5,000 procedures per year. The three reflections below are the ones I most often share with new physicians. I hope they make your journey smoother.

1. Instruments: gentleness goes further than sharpness

When I first began performing vasectomies, I assumed my instruments needed to be extremely sharp to deliver consistent, high-quality results. I purchased 10 full kits, had the hemostats sharpened professionally once, and even sharpened them myself later on.

But something changed with experience.

After a few hundred vasectomies, I learned to handle my instruments with more finesse—during use, during cleaning, and during sterilization. To my surprise, I discovered that you don’t actually need razor-sharp hemostats to perform vasectomies efficiently. In fact, in the past seven years, I haven’t had to sharpen them at all.

I’ve also never replaced a kit because of damage. Any expansion of my instrument inventory has been driven purely by patient demand and the need to accommodate higher volumes—not because instruments wore out.

Takeaway:

→ Don’t overthink instrument sharpness. Focus instead on gentle technique and careful handling. Well-maintained tools will last much longer than you expect.

2. Track your practice data early — even if your system evolves

Like many of you, I began by tracking outcomes using Word tables and Excel spreadsheets. When I was doing a relatively small number of procedures, that worked well enough.

But once I started scaling, I quickly realized that good data systems become essential—not optional.

Today, I rely on the analytics features built into my EMR (I use CHR by Telus Health). It’s more expensive than some other platforms, but at 4,000–5,000 procedures per year, it’s the only realistic way for me to:

- Track complication rates

- Monitor infection trends

- Measure efficiency

- Analyze workflow

- Identify opportunities for improvement

Whatever system you start with, the key is consistency. Develop the habit of documenting your outcomes early, even if the platform changes over time.

Takeaway:

→ Build a culture of data tracking from day one. Your future self—and your patients—will thank you.

3. Managing wait times while balancing a blended practice

Many new vasectomists are family physicians or generalists incorporating procedural work into their clinical week. I was one of them. For 3–4 years, I practiced both full-scope family medicine and vasectomies.

Over time, I realized how much I enjoyed procedural care. Gradually, I reduced my family medicine commitments, transferring patients to trusted colleagues and freeing up time to increase my vasectomy volume.

During that transition, wait-time management became critical. My goal was always to keep the waiting list under three months from referral to procedure. For Canadian patients, this feels very reasonable and improves the overall experience.

As my procedural practice grew, I eventually shifted entirely away from family medicine. Today, my work is focused on vasectomies, vasectomy reversals, circumcisions, and related urological procedures.

Takeaway:

→ If you’re building a vasectomy practice while still doing primary care, be intentional about your scheduling and wait-time management. A gradual shift can be healthy—for you, your patients, and your clinic.

Closing Thoughts

Starting a vasectomy practice is not just about mastering a technique—it’s about building sustainable systems, nurturing good habits, and adapting as your volume grows. Experience will shape your workflow, but shared wisdom can make that journey faster, smoother, and safer.

If you’re a young physician entering this field, welcome. It’s meaningful, efficient, patient-centered work—and an incredibly rewarding way to contribute to global reproductive health.

Clinical Update after 500 Vasectomies

Devon Turner, Barrie, Ontario, Canada

Oct 9, 2025, 9:10:15 AM

Hello colleagues!

I am writing to share a bit of my experience from my last update, which I hope will be of value to those who are starting their vasectomy practices.

A brief summary: I practice in Barrie, Ontario, Canada. I started offering vasectomies in 2023 after training with Michel ( Labrecque) and Doug (Stein). I run a family practice and do vasectomies as an additional skill within the same practice setting. I started doing vasectomies after only doing the rare minor procedure in my office, so I came to it from a very non-surgical medical background. I wrote a note to this group after completing about 150 vasectomies.

I’m now at over 500 procedures, and am comfortable in saying that I do an efficient, low-sensory high quality vasectomy. At this point most of the procedures I do feel very straightforward. The ones that are challenging I now believe would be challenging for many people, and I get a sense of accomplishment when I finish them rather than rethink my career choices as I am struggling away (which I did often in the first 100). My worries about complication rates have been put to rest; I’m sure everyone starting out worries that they will somehow have a worse complication rate than everyone else. I think the beauty of this procedure is that if you are trained well, and take your time with your first hundred or so procedures, then you’ll have the skill to let the procedure just do what it does – high success rates with minimal complications.

In each case of the complications I have had, there has been an unanticipated variable that has come up (e.g. – the guy with the hematoma took an axe to his neighbour’s car 8 hours after his vasectomy. So I was less disappointed about the hematoma and more impressed that he was so pain free he had the energy to take the axe to the neighbour’s car).

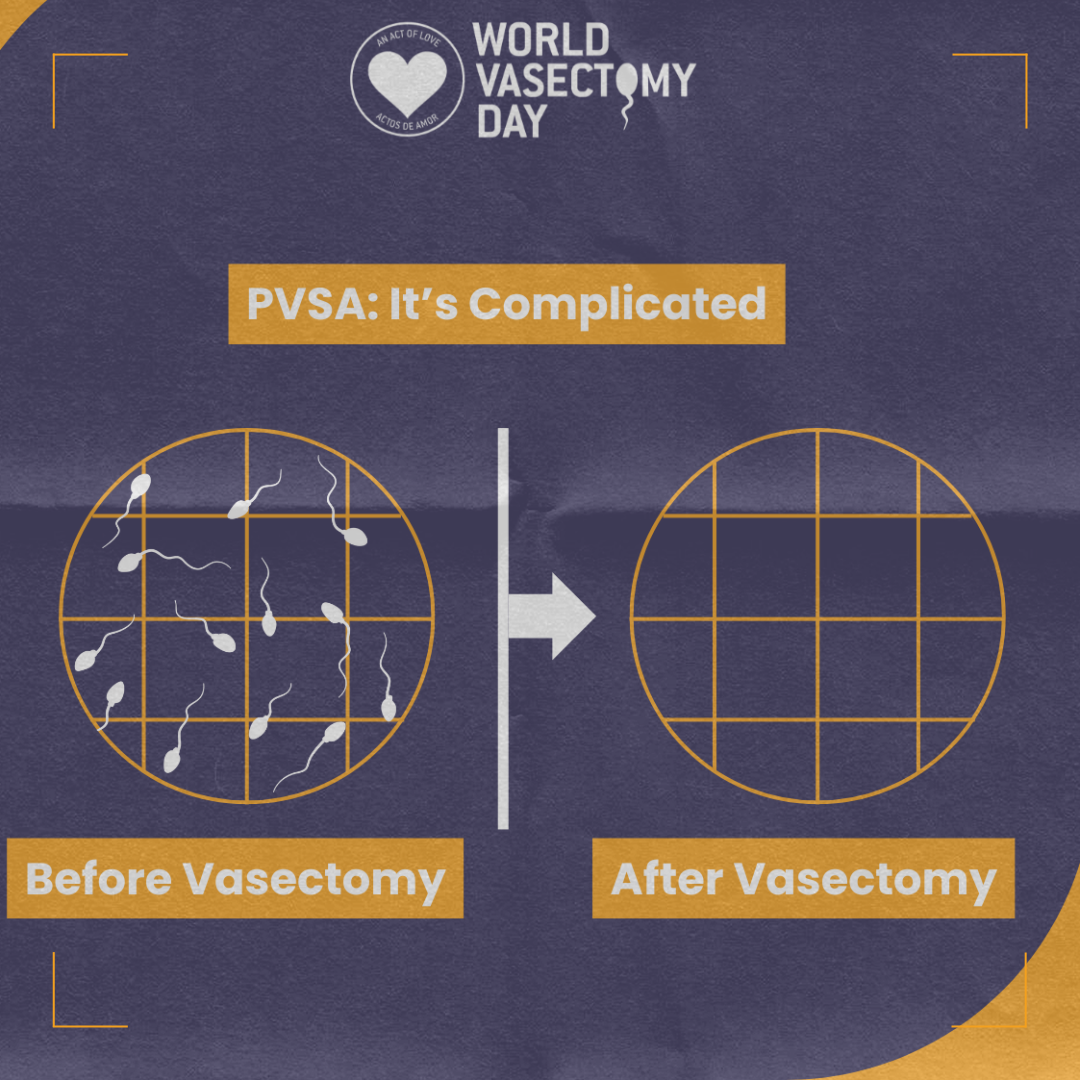

I have prescribed antibiotics four times so far and am unconvinced that they were true infections. I have prescribed an anti-inflammatory for about 20 patients or so for either worsening pain a week or so after their procedure or greater-than-typical swelling at the vas division site. I have had two people I have managed as PVPS so far and their symptoms have eventually settled down. I have one confirmed failure at 3 months on my 30th vasectomy in a guy who had two previous scrotal surgeries, with an eventual successful repeat.

I don’t think I have been practicing long enough to get a sense of the late failure rate so that remains a point of uncertainty for me. I think these complication numbers are lower than the reported rates in the literature, and I share them not with an intent to draw attention to that because I truly do not believe there is anything special about my skill, but I do think it reflects that the training I received was strong and that the approach to really take my time with my first 100 procedures and learn from what did not go well pays off and leads to a safe and effective vasectomy.

When I started, I was very worried about what my complications would be and what they would say about my skill and my ability to do this long term. I am still of course worried about complications, but I have relaxed a bit about them now as I know they are part of the process. For me, having these complications and working through them has been a critical component to building confidence and knowledge base from which to counsel as see new consults and seek to answer their questions accurately.

Keeping and analyzing data has been extremely valuable. One of the data points I track is my procedural abandonment rate – these are procedures I start which for some reason I do not finish. For me I think it reflects both my skill and my confidence. Seeing it go down over time has been a confidence builder: 9.5% for the first 100 procedures; 3.6% from 100-300, and 1.3% from 300-500. The number of consults for whom I decline to do their procedure has also dropped significantly over that same time frame, with only a handful of individuals so far this year that I have turned away due to the nature of their exam.

While the first few years for me were focused squarely on developing the skill, my focus is now on practice management. I do not work with an assistant other than setting up my tray but am now finally booking 30 minutes for the procedures and 15 minutes for consults. (I started at 60 and 30 respectively). I still do them as separate visits because that is what works well for me. I rely heavily on my website which has written information and videos (thanks to the nudging of Kevin Christie) to help streamline the process. I am fastidious with my communication to patients, from what I want them to consider for recovery to following up after the procedure. Everyone gets my number, everyone gets a follow up phone call to check on recovery. I have not had an instance where patients having my number has been a problem, and they have been incredibly grateful for it and respectful of it when they have reached out.

For those who have a blended practice like mine, I am constantly trying to balance my family practice availability with my vasectomy availability and I suspect that will be a constant juggle. I had the great fortune to attend the ski seminar in 2024 which was incredibly valuable for me, particularly at that time in my skill and practice development.

In summary, my advice to anyone starting out:

- Get trained well, but do not expect to feel like a pro after your training. It took me 100 to feel comfortable and I had imposter syndrome. At 500 I feel completely legitimate doing vasectomies. I’ll probably wait until I’m at a 4 or 5-digit procedure count before I even consider using the word pro, but am looking forward to getting there :).

- Track your data and review it regularly. Keep a record of why you chose to refer elsewhere, your abandonment rate and your complications. Referring to these at various stages has been very helpful for me.

- Use the vasectomy group archives to answer and research many of your questions.*

I welcome anyone’s thoughts on my experience, advice based on what I have shared, and would be very interested to know if my experience resonates with that of other new vasectomists.

For those of you who have read this far, a few questions I would put to the group*:

- How often do you buy new instruments to replace your existing ones, specifically sharp hemostats? I’ve tried to sharpen mine but I think I probably just need to replace them.

- What do you use to track your practice data? I use a Numbers spreadsheet, as my EMR does not allow for the granular detail I want to track. It is tedious but worth it, but as my referral count grows I see an eventual need to move to something different.

- Those who have a blended practice – how do you manage growing wait times for procedures? I am the only one in my community doing vasectomies, and now have a wait time of 3-4 months for a consult and 3-4 months thereafter for the procedure, as I do have to balance my time with my obligations to my family practice.

Thanks for reading, and thank you for the continued discussion this group provides!*

Devon

*[note to practitioners who may not belong to the Vasectomy Google Group and wish to join, please send an email request to Doug Stein at steinmail@vasweb.com ]

Clarity When Ordering Instruments

John Curington, Gentle Vasectomy, Sarasota, FL, USA

Sep 22, 2025, 10:10:39 AM

Hi Friends,

I’ve just returned from an international trip where we trained new vasectomy physicians. While helping with instrument orders, I was reminded how confusing this process can be – especially at the start, when you may not even know exactly what instruments come in a decent, complete vasectomy set. Even experienced vasectomists sometimes struggle with ordering, since there’s no universally accepted “standard set.”

Over the years, I’ve received many variations when ordering instruments:

- Ring forceps with ring diameters of 2.9mm, 3.5mm, 4.1mm, and 5.0mm.

- Scissors ranging from lightweight, straight and curved to heavyweight Mayo-style operating scissors.

- Hemostats in different handle lengths, tip shapes, and both straight and curved versions.

All of these came from the same excellent supplier – but because I didn’t specify exactly what I wanted, they had no way of knowing. I’ve attached photos of the different forceps and scissors I’ve received. (As for hemostats, I gave away the ones I didn’t like – friends now use them for tying fishing lures and other odd jobs).

After years of trial and error, I’ve learned the value of being very clear from the start. My recent orders have gone more smoothly because I specify exactly what I want.

Here’s my current standard kit:

- Vasectomy ring forceps, 3.5mm ring

- Vasectomy dissecting forceps (Li dissecting forceps)

- Surgical operating scissors, heavyweight, 145mm, straight, sharp-sharp tips

- Mosquito forceps (Halsted 140mm straight with fine tip)

This isn’t meant to be the ideal kit for everyone. The key takeaway is: if you clearly specify what you want, you’ll get the right instruments – without ending up with a drawer full of “almost right” ones.

I hope this is useful to someone,

John